Subordinate Clauses Represent Complete Thoughts

In syntax, verb-second (V2) discussion order [i] is a sentence structure in which the main verb (the finite verb) of a judgement or a clause is placed in the clause's second position, so that the verb is preceded by a single discussion or group of words (a single constituent).

Examples of V2 in English include (brackets indicating a unmarried constituent):

- "Neither practise I", "[Never in my life] have I seen such things"

If English used V2 in all situations, the post-obit would exist right:

- "*[In schoolhouse] learned I about animals", "*[When she comes home from work] takes she a nap"

V2 word social club is common in the Germanic languages and is also found in Northeast Caucasian Ingush, Uto-Aztecan O'odham, and fragmentarily in Romance Sursilvan (a Rhaeto-Romansh multifariousness) and Finno-Ugric Estonian.[2] Of the Germanic family, English is exceptional in having predominantly SVO gild instead of V2, although there are vestiges of the V2 phenomenon.

Most Germanic languages do not normally utilize V2 guild in embedded clauses, with a few exceptions. In item, German language, Dutch, and Afrikaans revert to VF (verb terminal) discussion social club later a complementizer; Yiddish and Icelandic practise, nonetheless, permit V2 in all declarative clauses: main, embedded, and subordinate. Kashmiri (an Indo-Aryan linguistic communication) has V2 in 'declarative content clauses' simply VF order in relative clauses.

Examples of verb second (V2) [edit]

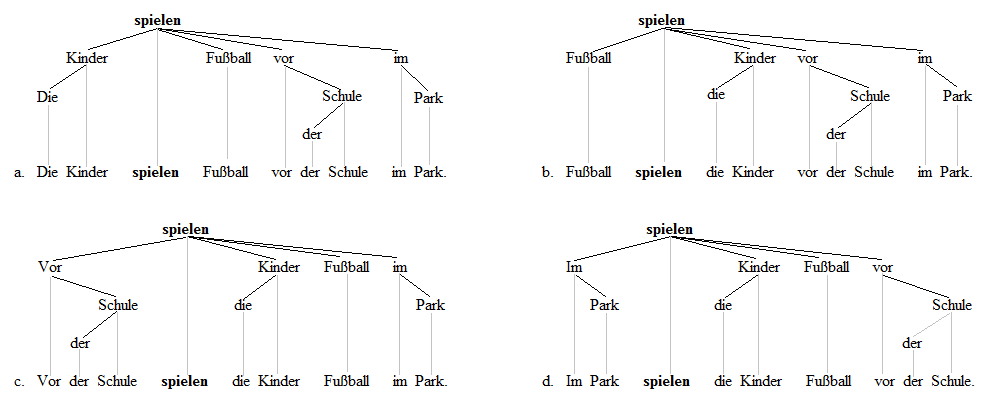

The example sentences in (one) from German illustrate the V2 principle, which allows any constituent to occupy the first position as long as the second position is occupied by the finite verb. Sentences (1a) through to (1d) have the finite verb spielten 'played' in 2nd position, with various constituents occupying the first position: in (1a) the subject field is in get-go position; in (1b) the object is; in (1c) the temporal modifier is in commencement position; and in (1d) the locative modifier is in start position. Sentences (1e) and (1f) are ungrammatical because the finite verb no longer appears in the 2d position. (An asterisk (*) indicates that an example is grammatically unacceptable.)

(1) (a) Die Kinder spielten vor der Schule im Park Fußball. The children played earlier schoolhouse in the park Soccer (b) Fußball spielten die Kinder vor der Schule im Park. Soccer played the children before school in the park (c) Vor der Schule spielten die Kinder im Park Fußball. Before school played the children in the park soccer. (d) Im Park spielten die Kinder vor der Schule Fußball. In the park played the children earlier schoolhouse soccer. (due east) *Vor der Schule Fußball spielten die Kinder im Park. Before school soccer played the children in the park (f) *Fußball die Kinder spielten vor der Schule im Park. Soccer the children played before school in the park.

Classical accounts of verb second (V2) [edit]

In major theoretical enquiry on V2 properties, researchers discussed that verb-final orders plant in High german and Dutch embedded clauses suggest that at that place is an underlying SOV order with specific syntactic movements rules that changes the underlying SOV order to derive a surface course where the finite verb is in the second position of the clause.[iii]

We first meet a "verb preposing" rule which moves the finite verb to the left most position in judgement, and so a "constituent preposing" rule which moves a constituent in front end of the finite verb. Following these ii rules will always result with the finite verb in 2d position.

"I like the man" (a) Ich den Mann mag --> Underlying form in Modern German I the human like (b) magazine ich den Isle of man --> Verb motility to left border like I the man (c) den Isle of mann mag ich --> Constituent moved to left border the man like I

Non-finite verbs and embedded clauses [edit]

Non-finite verbs [edit]

The V2 principle regulates the position of finite verbs simply; its influence on non-finite verbs (infinitives, participles, etc.) is indirect. Not-finite verbs in V2 languages appear in varying positions depending on the language. In German language and Dutch, for example, not-finite verbs appear after the object (if one is present) in clause concluding position in primary clauses (OV order). Swedish and Icelandic, in contrast, position non-finite verbs after the finite verb merely before the object (if one is present) (VO social club). That is, V2 operates on only the finite verb.

V2 in embedded clauses [edit]

(In the following examples, finite verb forms are in bold, non-finite verb forms are in italics and subjects are underlined.)

Germanic languages vary in the application of V2 gild in embedded clauses. They autumn into iii groups.

V2 in Swedish, Danish, Norwegian, Faroese [edit]

In these languages, the word order of clauses is generally fixed in ii patterns of conventionally numbered positions.[4] Both end with positions for (five) non-finite verb forms, (half-dozen) objects, and (7), adverbials.

In main clauses, the V2 constraint holds. The finite verb must exist in position (2) and sentence adverbs in position (4). The latter include words with meanings such as 'non' and 'ever'. The subject may be position (1), only when a topical expression occupies the position, the subject is in position (3).

In embedded clauses, the V2 constraint is absent. After the conjunction, the discipline must immediately follow; information technology cannot exist replaced by a topical expression. Thus, the get-go 4 positions are in the fixed order (1) conjunction, (2) subject, (3) sentence adverb, (4) finite verb

The position of the judgement adverbs is important to those theorists who run into them every bit marking the offset of a big constituent within the clause. Thus the finite verb is seen as inside that constituent in embedded clauses, but outside that elective in V2 master clauses.

Swedish

-

main clause

embedded clauseFront end

—Finite verb

ConjunctionSubject

Subject fieldSentence adverb

Sentence adverb—

Finite verbNon-finite verb

Non-finite verbObject

ObjectAdverbial

Adverbialmain clause a. I dag ville Lotte inte läsa tidningen 1 ii 3 four five 6 today wanted Lotte non read the newspaper ... 'Lotte didn't want to read the paper today.' embedded clause b. att Lotte inte ville koka kaffe i dag 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 that Lotte not wanted brew coffee today ... 'that Lotte didn't want to make coffee today'

Main clause Front Finite verb Subject Sentence adverb __ Non-finite verb Object Adverbial Embedded clause __ Conjunction Subject field Sentence adverb Finite verb Not-finite verb Object Adverbial Main clause (a) I dag ville Lotte inte läsa tidningen today wanted Lotte not read the paper "Lotte didn't want to read the newspaper today." Embedded clause (b) att Lotte inte ville koka kaffe i dag that Lotte not wanted brew java today "that Lotte didn't want to make coffee today."

Danish

-

main clause

embedded clauseFront

—Finite verb

ConjunctionSubject

SubjectSentence adverb

Sentence adverb—

Finite verbNon-finite verb

Non-finite verbObject

ObjectAdverbial

Adverbialmain clause a. Klaus er ikke kommet 1 2 4 5 Klaus is not come ...'Klaus hasn't come.' embedded clause b. når Klaus ikke er kommet one ii 3 4 five when Klaus not is come ...'when Klaus hasn't come up'

And so-called Perkerdansk is an example of a variety that does not follow the above.

Norwegian

(with multiple adverbials and multiple non-finite forms, in two varieties of the language)

-

main

embeddedFront

—Finite verb

ConjunctionSubject

Subject fieldSentence adverb

Sentence adverb—

Finite verbNon-finite verb

Non-finite verbObject

ObjectAdverbial

Adverbialchief clause a. Den gangen hadde han dessverre ikke villet sende sakspapirene før møtet. (Bokmål diverseness) one 2 three 4 five 6 7 that time had he unfortunately not wanted to ship the documents earlier the coming together ... 'This time he had unfortunately not wanted

to ship the documents before the meeting.'embedded clause b. av di han denne gongen diverre ikkje hadde vilja senda sakspapira føre møtet. (Nynorsk multifariousness) i 2 iii iv 5 6 7 because he this time unfortunately not had wanted to send the documents before the meeting ... 'because this time he had unfortunately non wanted

to send the documents before the meeting.'

Faroese

Different continental Scandinavian languages, the sentence adverb may either precede or follow the finite verb in embedded clauses. A (3a) slot is inserted hither for the following sentence adverb alternative.

-

main clause

embedded clauseFront

—Finite verb

ConjunctionSubject

Subject areaJudgement adverb

Sentence adverb—

Finite verb—

Sentence adverbNon-finite verb

Non-finite verbObject

ObjectAdverbial

Adverbialmain clause a. Her man fólk ongantíð hava fingið fisk fyrr 1 two three 4 five 6 7 here must people never have caught fish earlier ... 'People have surely never defenseless fish hither earlier.' embedded clause b. hóast fólk ongantíð hevur fingið fisk her 1 2 three 4 5 half dozen 7 although people never have caught fish here c. hóast fólk hevur ongantíð fingið fisk her ane 2 4 (3a) 5 6 7 although people have never defenseless fish here ... 'although people have never caught fish hither'

V2 in High german [edit]

In main clauses, the V2 constraint holds. Every bit with other Germanic languages, the finite verb must be in the second position. Nevertheless, any non-finite forms must exist in last position. The subject may be in the first position, but when a topical expression occupies the position, the subject field follows the finite verb.

In embedded clauses, the V2 constraint does not hold. The finite verb form must be side by side to whatsoever not-finite at the end of the clause.

German grammarians traditionally divide sentences into fields. Subordinate clauses preceding the main clause are said to be in the first field (Vorfeld), clauses following the main clause in the terminal field (Nachfeld).

The central field (Mittelfeld) contains most or all of a clause, and is bounded by left bracket (Linke Satzklammer) and right subclass (Rechte Satzklammer) positions.

In master clauses, the initial chemical element (subject or topical expression) is said to be located in the first field, the V2 finite verb form in the left bracket, and any non-finite verb forms in the right bracket.

In embedded clauses, the conjunction is said to be located in the left bracket, and the verb forms in the correct bracket. In German embedded clauses, a finite verb form follows whatever non-finite forms.

German [5]

-

First field Left bracket Central field Right bracket Final field Main clause a. Er chapeau dich gestern nicht angerufen weil er dich nicht stören wollte. he has you lot yesterday not rung ... 'He didn't band you yesterday because he didn't want to disturb you.' b. Sobald er Zeit lid wird er dich anrufen Equally shortly as he has time will he you band ...'When he has time he will ring y'all.' Embedded clause c. dass er dich gestern nicht angerufen hat that he you yesterday not rung has ...'that he didn't ring you yesterday'

V2 in Dutch and Afrikaans [edit]

V2 word lodge is used in main clauses, the finite verb must exist in the second position. However, in subordinate clauses two word orders are possible for the verb clusters.

Main clauses:

Dutch [6]

-

First field Left bracket Central field Right bracket Final field Primary clause a. De Māori hebben Nieuw-Zeeland ontdekt The Māori have New Zealand discovered ...'The Māori discovered New Zealand.' b. Tussen ongeveer 1250 en 1300 ontdekten de Māori Nieuw-Zeeland Between approximately 1250 and 1300 discovered the Māori New Zealand ...'Between near 1250 and 1300, the Māori discovered New Zealand.' c. Niemand had gedacht dat ook maar iets zou gebeuren. Nobody had thought ...'Nobody figured that anything would happen.' Embedded clause d. dat de Māori Nieuw-Zeeland hebben ontdekt that the Māori New Zealand have discovered ...'that the Māori discovered New Zealand'

This assay suggests a close parallel between the V2 finite class in main clauses and the conjunctions in embedded clauses. Each is seen equally an introduction to its clause-type, a function which some modern scholars accept equated with the notion of specifier. The analysis is supported in spoken Dutch by the placement of clitic pronoun subjects. Forms such every bit ze cannot stand alone, unlike the full-course equivalent zij. The words to which they may exist attached are those same introduction words: the V2 grade in a main clause, or the conjunction in an embedded clause.[7]

-

Outset field Left subclass Central field Right bracket Final field Master clause eastward. Tussen ongeveer 1250 en 1300 ontdekten-ze Nieuw-Zeeland between approximately 1250 and 1300 discovered-they New Zealand ...'Between about 1250 and 1300, they discovered New Zealand.' Embedded clause f. dat-ze tussen ongeveer 1250 en 1300 Nieuw-Zeeland hebben ontdekt that-they betwixt approximately 1250 and 1300 New Zealand have discovered ...'that they discovered New Zealand between nigh 1250 and 1300'

Subordinate clauses:

In Dutch subordinate clauses two word orders are possible for the verb clusters and are referred to as the "red": omdat ik heb gewerkt, "considering I have worked": similar in English, where the auxiliary verb precedes the past particle, and the "dark-green": omdat ik gewerkt heb, where the by particle precedes the auxiliary verb, "because I worked have": like in German.[8] In Dutch, the green word order is the most used in speech communication, and the carmine is the most used in writing, particularly in journalistic texts, but the dark-green is also used in writing every bit is the red in speech communication. Different in English however adjectives and adverbs must precede the verb: ''dat het boek groen is'', "that the book green is".

-

First field Left bracket Cardinal field Correct bracket Final field Embedded clause g. omdat ik het dan gezien zou hebben most common in the Netherlands because I information technology then seen would accept h. omdat ik het dan zou gezien hebben nigh mutual in Belgium because I it then would seen have i. omdat ik het dan zou hebben gezien often used in writing in both countries, just common in speech as well, about common in Limburg because I it then would accept seen j. omdat ik het dan gezien hebben zou used in Friesland, Groningen and Drenthe, least common merely used besides because I it and then seen have would ...'because and so I would accept seen it'

V2 in Icelandic and Yiddish [edit]

These languages freely allow V2 social club in embedded clauses.

Icelandic

Two discussion-order patterns are largely similar to continental Scandinavian. Still, in chief clauses an extra slot is needed for when the front position is occupied by Það. In these clauses the subject follows any sentence adverbs. In embedded clauses, judgement adverbs follow the finite verb (an optional social club in Faroese).[9]

-

main clause

embedded clauseFront

—Finite verb

ConjunctionSubject area

Subject area—

Finite verbSentence adverb

Sentence adverbSubject field

—Non-finite verb

Not-finite verbObject

ObjectAdverbial

Adverbialmain clause a. Margir höfðu aldrei lokið verkefninu. Many had never finished the consignment ... 'Many had never finished the consignment.' b. Það höfðu aldrei margir lokið verkefninu. there have never many finished the assignment ... 'At that place were never many people who had finished the assignment.' c. Bókina hefur María ekki lesið. the volume has Mary non read ... 'Mary hasn't read the book.' embedded clause d. hvort María hefur ekki lesið bokina. whether Mary has not read the volume ... 'whether Mary hasn't read the book'

In more radical contrast with other Germanic languages, a third pattern exists for embedded clauses with the conjunction followed by the V2 gild: forepart-finite verb-discipline.[10]

-

Conjunction Front

(Topic adverbial)Finite verb Subject e. Jón efast um að á morgun fari María snemma á fætur. John doubts that tomorrow go Mary early on up ... 'John doubts that Mary will get up early on tomorrow.' Conjunction Front end

(Object)Finite verb Subject f. Jón harmar að þessa bók skuli ég hafa lesið. John regrets that this volume shall I have read ... 'John regrets that I accept read this book.'

Yiddish

Unlike Standard German, Yiddish normally has verb forms before Objects (SVO guild), and in embedded clauses has conjunction followed past V2 order.[11]

-

Front

(Subject area)Finite verb Conjunction Forepart

(Subject)Finite verb a. ikh hob gezen mitvokh, az ikh vel nit kenen kumen donershtik I accept seen Wednesday that I will not can come Thursday ... 'I saw on Wednesday that I wouldn't be able to come on Thursday.' Front

(Adverbial)Finite verb Field of study Conjunction Front end

(Adverbial)Finite verb Subject b. mitvokh hob ikh gezen, az donershtik vel ikh nit kenen kumen Wednesday take I seen that Thursday will I non can come ... On Wednesday I saw that on Th I wouldn't be able to come up.'

V2 in root clauses [edit]

One type of embedded clause with V2 following the conjunction is found throughout the Germanic languages, although it is more common in some than it is others. These are termed root clauses. They are declarative content clauses, the direct objects of and then-called bridge verbs, which are understood to quote a statement. For that reason, they showroom the V2 give-and-take order of the equivalent direct quotation.

Danish

Items other than the subject area are allowed to appear in forepart position.

-

Conjunction Forepart

(Subject)Finite verb a. 6 ved at Bo ikke har læst denne bog We know that Bo non has read this book ... 'Nosotros know that Bo has not read this book.' Conjunction Front

(Object)Finite verb Discipline b. Half dozen ved at denne bog har Bo ikke læst We know that this book has Bo not read ... 'Nosotros know that Bo has non read this volume.'

Swedish

Items other than the bailiwick are occasionally immune to appear in front position. Generally, the statement must exist one with which the speaker agrees.

-

Conjunction Front

(Adverbial)Finite verb Subject d. Jag tror att i det fallet har du rätt I think that in that respect have you right ... 'I think that in that respect you are right.'

This club is not possible with a statement with which the speaker does non concur.

-

Conjunction Front

(Adverbial)Finite verb Subject due east. *Jag tror inte att i det fallet har du rätt (The asterisk signals that the sentence is non grammatically adequate.) I think non that in that respect take y'all correct ... 'I don't think that in that respect yous are right.'

Norwegian

-

Conjunction Front

(Adverbial)Finite verb Subject f. hun fortalte at til fødselsdagen hadde hun fått kunstbok (Bokmål variety) she told that for her birthday had' she received art-volume ... 'She said that for her birthday she had been given a book on art.'

German

Root clause V2 gild is possible only when the conjunction dass is omitted.

-

Conjunction Front

(Subject)Finite verb g. *Er behauptet, dass er chapeau es zur Post gebracht (The asterisk signals that the sentence is not grammatically acceptable.) h. Er behauptet, er hat es zur Mail gebracht he claims (that) he has it to the post role taken ... 'He claims that he took it to the mail service office.'

Compare the normal embed-clause lodge subsequently dass

-

Left bracket

(Conjunction)Key field Right bracket

(Verb forms)i. Er behauptet, dass er es zur Postal service gebracht hat he claims that he it to the post office taken has

Perspective effects on embedded V2 [edit]

In that location are a limited number of V2 languages that can let for embedded verb motion for a specific businesslike outcome similar to that of English. This is due to the perspective of the speaker. Languages such as German and Swedish accept embedded verb second. The embedded verb second in these kinds of languages usually occur after 'bridge verbs'.[12]

(Bridge verbs are common verbs of spoken language and thoughts such as "say", "think", and "know", and the give-and-take "that" is not needed afterward these verbs. For example: I think he is coming.)

(a)

Jag ska säga dig att jag är inte ett dugg intresserad.

I will say you that I am not a dew interested.

"I tell you that I am non the to the lowest degree bit interested."

→ In this sentence, "tell" is the bridge verb and "am" is an embedded verb 2d.

Based on an exclamation theory, the perspective of a speaker is reaffirmed in embedded V2 clauses. A speaker's sense of commitment to or responsibility for V2 in embedded clauses is greater than a non-V2 in embedded clause.[13] This is the consequence of V2 characteristics. As shown in the examples below, there is a greater delivery to the truth in the embedded clause when V2 is in identify.

(a)

Maria denkt, dass Peter glücklich ist.

Maria thinks that Peter happy is

→ In a non-V2 embedded clause, the speaker is just committed to the truth of the statement "Maria thinks ..."

(b)

Maria denkt, Peter ist glücklich.

Maria thinks Peter is happy.

→ In a V2 embedded clause, the speaker is committed to the truth of the argument "Maria thinks ..." and also the proffer "Peter is happy".

Variations of V2 [edit]

Variations of V2 order such as V1 (verb-initial discussion order), V3 and V4 orders are widely attested in many Early Germanic and Medieval Romance languages. These variations are possible in the languages nevertheless it is severely restricted to specific contexts.

V1 word gild [edit]

V1 (verb-initial word order) is a type of structure that contains the finite verb as the initial clause element. In other words the verb appears before the subject and the object of the sentence.

(a) Max y-il [south no' tx;i;] [o naq Lwin]. (Mayan) PFV A3-meet CLF domestic dog CLF Pedro 'The dog saw Pedro.'

V3 word gild [edit]

V3 (verb-third give-and-take social club) is a variation of V2 in which the finite verb is in third position with two constituents preceding information technology. In V3, like in V2 give-and-take society, the constituents preceding the finite verb are not categorically restricted, equally the constituents tin can be a DP, a PP, a CP so on.[14]

(a)

[DP Jedes jahr] [Pn ich] kauf mir bei Deichmann

{} every yr {} I buy me at Deichmann

"Every yr I buy (shoes) at Deichmann's"

(b)

[PP ab jetzt] [Pn ich] krieg immer zwanzig Euro

{} from at present {} I get e'er 20 euros

"From now on, I always get twenty euros"

V2 and left border filling trigger (LEFT) [edit]

V2 is fundamentally derived from a morphological obligatory exponence effect at judgement level. The left edge filling trigger (LEFT) effects are unremarkably seen in classical V2 languages such as Germanic languages and Former Romance languages. The left edge filling trigger is independently active in morphology as EPP furnishings are constitute in give-and-take-internal levels. The obligatory exponence derives from accented displacement, ergative displacement and ergative doubling in inflectional morphology. In addition, second position rules in clitic 2d languages demonstrate post-syntactic rules of LEFT movement. Using the linguistic communication Breton as an example, absenteeism of a pre-tense expletive will permit for the LEFT to occur to avoid tense-get-go. The LEFT movement is free from syntactic rules which is evidence for a post-syntactic phenomenon. With the LEFT movement, V2 word order tin exist obtained as seen in the example beneath.[15]

(a)

Bez 'nevo hennex traou

EXPL Fin.[will.have] he things

"He will take goods"

In this Breton case, the finite caput is phonetically realized and agrees with the category of the preceding chemical element. The pre-tense "Bez" is used in front of the finite verb to obtain the V2 discussion order. (finite verb "nevo" is bolded).

Syntactic verb second [edit]

It is said that V2 patterns are a syntactic phenomenon and therefore have sure environments where it can and cannot be tolerated. Syntactically, V2 requires a left-peripheral head (unremarkably C) with an occupied specifier and paired with raising the highest verb-auxiliary to that head. V2 is usually analyzed every bit the co-occurrence of these requirements, which tin also exist referred to as "triggers". The left-peripheral head, which is a requirement that causes the effect of V2, sets farther requirements on a phrase XP that occupies the initial position, so that this phrase XP may always have specific featural characteristics. [16]

V2 in English language [edit]

Mod English language differs profoundly in give-and-take order from other modern Germanic languages, only earlier English language shared many similarities. For this reason, some scholars propose a clarification of Old English with V2 constraint equally the norm. The history of English syntax is thus seen as a process of losing the constraint.[17]

Quondam English language [edit]

In these examples, finite verb forms are in greenish, non-finite verb forms are in orange and subjects are blue.

Main clauses [edit]

a.

Discipline first

Se mæssepreost sceal manum bodian þone soþan geleafan

the masspriest shall people preach the truthful faith

'The mass priest shall preach the true organized religion to the people.'

b.

Question word offset

Hwi wolde God swa lytles þinges him forwyrman

Why would God so small thing him deny

'Why would God deny him such a small thing?'

c.

Topic phrase showtime

on twam þingum hæfde God þæs mannes sawle geododod

in 2 things has God the man's soul endowed

'With 2 things God had endowed homo'south soul.'

d.

þa first

þa wæs þæt folc þæs micclan welan ungemetlice brucende

then was the people of-the keen prosperity excessively partaking

'Then the people were partaking excessively of the cracking prosperity.'

e.

Negative discussion starting time

Ne sceal he naht unaliefedes don

not shall he nil unlawful do

'He shall not practise anything unlawful.'

f.

Object first

Ðas ðreo ðing forgifð God he gecorenum

these iii things gives God his chosen

'These three things God gives to his chosen

Position of object [edit]

In examples b, c and d, the object of the clause precedes a non-finite verb form. Superficially, the structure is verb-field of study-object- verb. To capture generalities, scholars of syntax and linguistic typology care for them as basically subject-object-verb (SOV) structure, modified past the V2 constraint. Thus One-time English is classified, to some extent, as an SOV language. However, example a represents a number of Old English clauses with object following a non-finite verb form, with the superficial structure verb-subject-verb object. A more substantial number of clauses contain a single finite verb course followed by an object, superficially verb-bailiwick-object. Again, a generalisation is captured by describing these as subject–verb–object (SVO) modified by V2. Thus Old English can be described as intermediate betwixt SOV languages (like German language and Dutch) and SVO languages (like Swedish and Icelandic).

Effect of field of study pronouns [edit]

When the subject of a clause was a personal pronoun, V2 did not e'er operate.

grand.

forðon nosotros sceolan mid ealle modernistic & mægene to Gode gecyrran

therefore nosotros must with all mind and power to God turn

'Therefore, nosotros must turn to God with all our mind and power

All the same, V2 verb-subject inversion occurred without exception after a question give-and-take or the negative ne, and with few exceptions after þa even with pronominal subjects.

h.

for hwam noldest þu {ðe sylfe} me gecgyðan þæt...

for what not-wanted you yourself me brand-downwards that...

'wherefore would you non want to make known to me yourself that...'

i.

Ne sceal he naht unaliefedes don

not shall he naught unlawful practise

'He shall not practise anything unlawful.'

j.

þa foron hie mid þrim scipum ut

then sailed they with three ships out

'So they sailed out with 3 ships.'

Inversion of a subject field pronoun besides occurred regularly later a directly quotation.[18]

grand.

"Me is," cwæð hēo Þīn cyme on miclum ðonce"

{to me} is said she your coming in much thankfulness

'"Your coming," she said, "is very gratifying to me".'

Embedded clauses [edit]

Embedded clauses with pronoun subjects were not subject to V2. Fifty-fifty with noun subjects, V2 inversion did not occur.

l.

leorningcnichtas

disciples

...þa ða his leorningcnichtas hine axodon for hwæs synnum se human wurde swa blind acenned

...when his disciples him asked for whose sins the man became thus blind {}

'...when his disciples asked him for whose sins the man was thus born blind'

Yes-no questions [edit]

In a similar clause pattern, the finite verb class of a yes-no question occupied the get-go position

m.

Truwast ðu nu þe selfum and þinum geferum bet þonne ðam apostolum...?

trust you now you self and your companions better than the apostles

'Do y'all now trust yourself and your companions better than the apostles...?'

Heart English [edit]

Continuity [edit]

Early Middle English generally preserved V2 structure in clauses with nominal subjects.

a.

Topic phrase first

On þis gær wolde þe king Stephne tæcen Rodbert

in this year wanted the king Stephen seize Robert

'During this twelvemonth King Stephen wanted to seize Robert.'

b.

Nu first

Nu loke euerich man toward himseleun

now look every human being to himself

'Now it'southward for every man to look to himself.'

Every bit in Old English, V2 inversion did non employ to clauses with pronoun subjects.

c.

Topic phrase first

bi þis ȝe mahen seon ant witen...

by this you may run into and know

d.

Object showtime

alle ðese bebodes ic habbe ihealde fram childhade

all those commandments I have kept from childhood

Change [edit]

Late Middle English texts of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries show increasing incidence of clauses without the inversion associated with V2.

e.

Topic adverb offset

sothely se ryghtwyse sekys þe loye and...

Truly the righteous seeks the joy and...

f.

Topic phrase first

And by þis same skyle hop and sore shulle jugen the states

And by this aforementioned skill hope and sorrow shall gauge us

Negative clauses were no longer formed with ne (or na) as the first chemical element. Inversion in negative clauses was owing to other causes.

g.

Wh- question give-and-take first

why ordeyned God not such ordre

why ordained God not such order

'Why did God not ordain such an order?' (non follows noun phrase subject)

h.

(not precedes pronoun subject field)

why shulde he not...

why should he not

i.

There starting time

Ther nys nat oon kan war by other be

there not-is not i tin can aware by other be

'In that location is not a single person who learns from the mistakes of others'

j.

Object get-go

He was despeyred; {no thyng} dorste he seye

He was {in despair}; nothing dared he say

Vestiges in Modern English [edit]

As in earlier periods, Modern English normally has subject-verb gild in declarative clauses and inverted verb-field of study order[19] in interrogative clauses. Nonetheless these norms are observed irrespective of the number of clause elements preceding the verb.

Classes of verbs in Mod English: auxiliary and lexical [edit]

Inversion in Old English sentences with a combination of 2 verbs could be described in terms of their finite and non-finite forms. The word which participated in inversion was the finite verb; the verb which retained its position relative to the object was the not-finite verb. In most types of Modern English clause, there are 2 verb forms, but the verbs are considered to belong to different syntactic classes. The verbs which participated in inversion take evolved to form a class of auxiliary verbs which may mark tense, aspect and mood; the remaining majority of verbs with full semantic value are said to plant the course of lexical verbs. The infrequent type of clause is that of declarative clause with a lexical verb in a present unproblematic or past simple form.

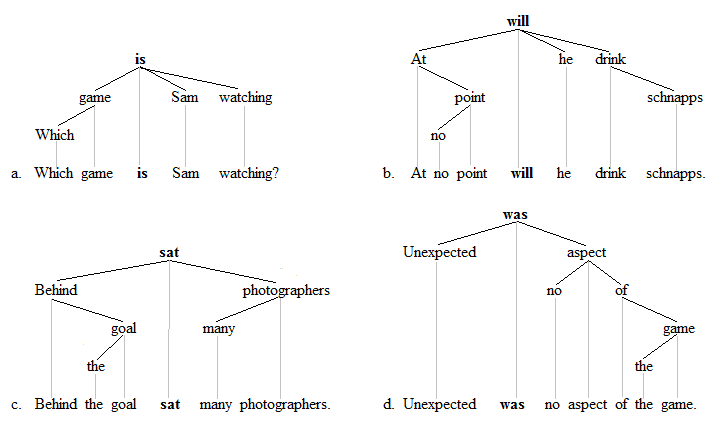

Questions [edit]

Like Yeah/No questions, interrogative Wh- questions are regularly formed with inversion of subject and auxiliary. Nowadays Elementary and By Simple questions are formed with the auxiliary practise, a process known as do-support.

-

a. Which game is Sam watching? b. Where does she live?

-

-

- (run into subject-auxiliary inversion in questions)

-

With topic adverbs and adverbial phrases [edit]

In certain patterns like to Old and Middle English language, inversion is possible. However, this is a matter of stylistic choice, unlike the constraint on interrogative clauses.

negative or restrictive adverbial first

-

c. At no point will he potable Schnapps. d. No sooner had she arrived than she started to make demands.

-

-

- (see negative inversion)

-

comparative adverb or adjective outset

-

e. So keenly did the children miss their parents, they cried themselves to sleep. f. Such was their sadness, they could never savor going out.

Later the preceding classes of adverbial, only auxiliary verbs, non lexical verbs, participate in inversion

locative or temporal adverb outset

-

g. Here comes the bus. h. Now is the 60 minutes when we must say adieu.

prepositional phrase starting time

-

i. Behind the goal sat many photographers. j. Down the route came the person we were waiting for.

-

-

- (see locative inversion, directive inversion)

-

After the ii latter types of adverbial, only one-word lexical verb forms (Nowadays Simple or Past Unproblematic), not auxiliary verbs, participate in inversion, and only with noun-phrase subjects, not pronominal subjects.

Direct quotations [edit]

When the object of a verb is a verbatim quotation, it may precede the verb, with a result like to Sometime English V2. Such clauses are found in storytelling and in news reports.

-

chiliad. "Wolf! Wolf!" cried the boy. l. "The unrest is spreading throughout the land," writes our Dki jakarta correspondent.

-

-

- (see quotative inversion)

-

Declarative clauses without inversion [edit]

Respective to the above examples, the following clauses show the normal Modern English subject-verb order.

Declarative equivalents

-

a′. Sam is watching the Loving cup games. b′. She lives in the country.

Equivalents without topic fronting

-

c′. He will at no point potable Schnapps. d′. She had no sooner arrived than she started to make demands. eastward′. The children missed their parents so keenly that they cried themselves to sleep. g′. The bus is coming hither. h′. The hour when nosotros must say goodbye is now. i′. Many photographers sat backside the goal. j′. The person we were waiting for came down the road. 1000′. The boy cried "Wolf! Wolf!" 50′. Our Djakarta contributor writes, "The unrest is spreading throughout the country" .

French [edit]

Modern French is a subject area-verb-object (SVO) language like other Romance languages (though Latin was a discipline-object-verb linguistic communication). Nonetheless, V2 constructions existed in Old French and were more mutual than in other early Romance language texts. It has been suggested that this may be due to influence from the Germanic Frankish language.[twenty] Modern French has vestiges of the V2 organisation similar to those found in modern English.

The following sentences have been identified every bit possible examples of V2 syntax in Old French:[21]

-

a. Sometime French Longetemps fu ly roys Elinas en la montaigne Modernistic French Longtemps fut le roi Elinas dans la montagne .... 'Pendant longtemps le roi Elinas a été dans les montagnes.' English For a long time was the king Elinas in the mountain ... 'King Elinas was in the mountains for a long time.'

-

b. Old French Iteuses paroles distrent li frere de Lancelot Modern French Telles paroles dirent les frères de Lancelot .... 'Les frères de Lancelot ont dit ces paroles' English Such words uttered the brothers of Lancelot .... 'Lancelot's brothers spoke these words.'

-

c. Old French Atant regarda contreval la mer Modern French Alors regarda en bas la mer .... 'Alors Il a regardé la mer plus bas.' English language So looked at downward the sea .... 'Then he looked down at the sea.' (Elision of subject area pronoun, opposite to the general rule in other Quondam French clause structures.)

Old French [edit]

Similarly to Modernistic French, Quondam French allows a range of constituents to precede the finite verb in the V2 position.

(1)

Il oste ses armes

He removes.3sg his weapons

'He removes his weapons'

Onetime Occitan [edit]

A language that is compared to Old French is Sometime Occitan, which is said to be the sister of Erstwhile French. Although the two languages are thought to be sister languages, Onetime Occitan exhibits a relaxed V2 whereas Old French has a much more strict V2. However, the differences between the two languages extend past V2 and also differ in a variation of V2, which is V3. In both linguistic communication varieties, occurrence of V3 can be triggered past the presence of an initial frame-setting clause or adverbial (1).

(ane)

Motorcar s'il ne me garde de pres, je ne dout mie

For if-he NEG me.CL= look.3SG of close I NEG dubiousness.1SG NEG

'Since he watches me and then closely, I do not dubiousness'

Other languages [edit]

Kotgarhi and Kochi [edit]

In his 1976 three-volume report of two languages of Himachal Pradesh, Hendriksen reports on two intermediate cases: Kotgarhi and Kochi. Although neither linguistic communication shows a regular V-two blueprint, they take evolved to the point that main and subordinate clauses differ in word order and auxiliaries may separate from other parts of the verb:

(a)

hyunda-baassie

winter-afterwards

hyunda-baassie jaa gõrmi hõ-i

winter-after goes summer become-GER

"Subsequently winter comes summer." (Hendriksen III:186)

Hendriksen reports that relative clauses in Kochi prove a greater tendency to have the finite verbal element in clause-concluding position than matrix clauses exercise (III:188).

Ingush [edit]

In Ingush, "for primary clauses, other than episode-initial and other all-new ones, verb-2d order is most common. The verb, or the finite role of a compound verb or analytic tense grade (i.eastward. the light verb or the auxiliary), follows the first word or phrase in the clause."[22]

(a)

muusaa vy hwuona telefon jettazh

Musa V.PROG 2sg.DAT telephone striking

'Musa is telephoning y'all.'

O'odham [edit]

O'odham has relatively free V2 word gild inside clauses; for example, all of the following sentences mean "the male child brands the hog":[23]

ceoj ʼo g ko:jĭ ceposid ko:jĭ ʼo one thousand ceoj ceposid ceoj ʼo ceposid g ko:jĭ ko:jĭ ʼo ceposid g ceoj ceposid ʼo yard ceoj m ko:jĭ ceposid ʼo g ko:jĭ g ceoj The finite verb is "'o" which appears after a constituent, in second position

Despite the general freedom of sentence word order, O'odham is adequately strictly verb-second in its placement of the auxiliary verb (in the in a higher place sentences, it is ʼo; in the post-obit it is ʼañ):

Affirmative: cipkan ʼañ = "I am working" Negative: pi ʼañ cipkan = "I am not working" [not *pi cipkan ʼañ]

Sursilvan [edit]

Among dialects of the Romansh, V2 word order is limited to Sursilvan, the insertion of entire phrases between auxiliary verbs and participles occurs, as in 'Cun Mariano Tschuor ha Augustin Beeli discurriu ' ('Mariano Tschuor has spoken with Augustin Beeli'), as compared to Engadinese 'Cun Rudolf Gasser ha discurrü Gion Peider Mischol' ('Rudolf Gasser has spoken with Gion Peider Mischol'.)[24]

The constituent that is divisional by the auxiliary, ha, and the participle, discurriu, is known every bit a Satzklammer or 'verbal bracket'.

Estonian [edit]

In Estonian, V2 give-and-take order is very frequent in the literate annals, but less frequent in the spoken register. When V2 order does occur, it is found in main clauses, as illustrated in (1).

(1)

koolimaja-st.

schoolhouse-ELA

Kiiresti lahku-s-id õpilase-d koolimaja-st.

speedily leave-PST-3PL pupil-NOM.PL school-ELA

'The students departed quickly from the school.'

Unlike Germanic V2 languages, Estonian has several instances where V2 discussion order is non attested in embedded clauses, such as wh-interrogatives (2), exclamatives (iii), and non-field of study-initial clauses (iv). [25]

(2)

Kes mei-le täna külla tule-b?

who.NOM. we-ALL today hamlet/visit.ILL come up-PRS.3SG

'Who will visit us today?'

(3)

Küll ta täna tule-b.

ADV s/he.NOM today come-PRS.3SG

'S/he's certain to come today!'

(4)

Täna ta mei-le külla ei tule.

today south/he.NOM we-ALL village/visit.ILL not come

'Today due south/he won't come to visit us.'

Welsh [edit]

In Welsh, V2 word order is found in Centre Welsh, just not in One-time and Modern Welsh which but has verb-initial order.[26] Heart Welsh displays 3 characteristics of V2 grammar:

(1) A finite verb in the C-domain (ii) The constituent preceding the verb can be whatever constituent (oft driven by businesslike features). (3) Only one constituent preceding the verb in subject area position

As nosotros can come across in the examples of V2 in Welsh below, at that place is merely ane constituent preceding the finite verb, but whatsoever kind of constituent (such equally a substantive phrase NP, adverb phrase AP and preposition phrase PP) can occur in this position.

(a)

[DP 'r guyrda a] doethant {y gyt}.

{} the nobles PRT came together.

"The nobles came together"

→ This judgement has a constituent with a subject, followed by the verb in 2nd position.

(b)

[DP deu drws a] welynt yn agoret.

{} two door PRT saw PRED open.

"They saw two doors that were open"

→ This sentence has a constituent with a object, followed by the verb in 2d position.

(c)

[AdvP yn diannot y] doeth tan o r nef.

{} PRED firsthand PRT came fire from the sky.

"They fabricated for the hall"

→ This sentence has a elective that is an adverb phrase, followed by the verb in second position.

(d)

[PP y r neuad y] kyrchyssant.

{} to the hall PRT went.

"They fabricated for the hall"

→ This sentence has a constituent that is a preposition phrase, followed by the verb in second position.

Centre Welsh tin as well exhibit variations of V2 such as cases of V1 (verb-initial give-and-take order) and V3 orders. Nonetheless, these variations are restricted to specific contexts such as in sentences that has impersonal verbs, imperatives, answers or direct responses to questions or commands and idiomatic sayings. It is too possible to take a preverbal particle preceding the verb in V2, withal these kind of sentences are limited besides.

Wymysorys [edit]

Wymysory is classified as a Due west-Germanic language, even so it can showroom various Slavonic characteristics. It is argued that Wymysorys enables its speaker to operate betwixt 2 give-and-take lodge system that represent two forces driving the grammar of this language Germanic and Slavonic. The Germanic arrangement is not as flexible and allows for V2 order to exist in it form while the Slavonic system is relatively gratuitous. Due to the rigid word order in the Germanic organisation, the placement of the verb is determines by syntactic rules in which V2 word order is commonly respected. [27]

Wymysory, like with other languages that exhibit V2 word order, the finite verb is in second position with a elective of whatever category preceding the verb such as DP, PP, AP so on.

(a)

[DP Der klop] kuzt wymyioerys.

{} The human speaks Wymysorys.

"The man speaks Wymysorys"

→ This judgement has a constituent with a field of study, followed by the verb in 2d position.

(b)

[DP Dos bihɫa] hot yh gyśrejwa.

{} This book had I written.

"I had written that book"

→ This sentence has a constituent with an object, followed past the verb in 2d position.

(c)

[PP Fjyr ejn] ej do.

{} For him is this.

"This is for him"

→ This sentence has a preposition phrase, followed by the verb in second position.

Classical Portuguese [edit]

Compared to other Romance languages, the V2 word society has existed in Classical Portuguese a lot longer. Although Classical Portuguese is a V2 language, V1 occurred more frequently and as a issue of this, it is argued whether or non Classical Portuguese actually is a V2-like language. However, Classical Portuguese is a relaxed V2 linguistic communication, meaning V2 patterns coexist with its variations, which are V1 and/or V3. In the case of Classical Portuguese, at that place is a strong relationship between V1 and V2 due to V2 clauses being derived from V1 clauses. In languages, such every bit Classical Portuguese, where both V1 and V2 be, both patterns depend on the movement of the verb to a high position of the CP layer, with the divergence existence whether or non a phrase is moved to a preverbal position. [28]

Although V1 occurred more frequently in Classical Portuguese, V2 is the more frequent order found in matrix clauses. Post-exact subjects may also occupy a high position in the clause and tin can precede VP adverbs. In (1) and (2), we tin see that the adverb 'bem' can precede or continue the post-verbal subject.

(ane)

E nos gasalhados e abraços mostraram os cardeais legados

and in-the welcome and greetings showed the cardinals delegates

'In the welcome and greetings the cardinal delegates showed this satisfaction well.'

(two)

Eastward quadra-Ihe bem o nome de Piemonte...

and fits-CL.3.DAT well the name of Piemonte

'And the proper name of Piemonte fits it well...'

In (two), the post-verbal subject is understood as an informational focus, just the same cannot be said for (1) considering the departure of the positions determine how the field of study is interpreted.

Structural assay of V2 [edit]

Various structural analyses of V2 accept been adult, including within the model of dependency grammar and generative grammar.

Structural analysis in dependency grammar [edit]

Dependency grammer (DG) can arrange the V2 phenomenon just past stipulating that one and only one constituent can be a predependent of the finite verb (i.due east. a dependent which precedes its caput) in declarative (matrix) clauses (in this, Dependency Grammar assumes simply ane clausal level and 1 position of the verb, instead of a stardom betwixt a VP-internal and a higher clausal position of the verb every bit in Generative Grammar, cf. the next section).[29] On this account, the V2 principle is violated if the finite verb has more than than one predependent or no predependent at all. The following DG structures of the commencement four German sentences above illustrate the analysis (the sentence means 'The kids play soccer in the park before school'):

The finite verb spielen is the root of all clause structure. The V2 principle requires that this root accept a single predependent, which it does in each of the four sentences.

The four English language sentences higher up involving the V2 phenomenon receive the following analyses:

Structural assay in generative grammar [edit]

In the theory of Generative Grammar, the verb second phenomenon has been described as an application of X-bar theory. The combination of a first position for a phrase and a second position for a single verb has been identified as the combination of specifier and head of a phrase. The part after the finite verb is and then the complement. While the sentence structure of English is commonly analysed in terms of three levels, CP, IP, and VP, in German linguistics the consensus has emerged that there is no IP in German.[30]

Tree structure for the English language clause. German does not use an "I" position and has a VP with the verb at the end.

The VP (verb phrase) construction assigns position and functions to the arguments of the verb. Hence, this structure is shaped by the grammatical properties of the V (verb) which heads the structure. The CP (complementizer phrase) construction incorporates the grammatical data which identifies the clause equally declarative or interrogative, chief or embedded. The structure is shaped by the abstract C (complementiser) which is considered the head of the construction. In embedded clauses the C position accommodates complementizers. In German declarative main clauses, C hosts the finite verb. Thus the V2 construction is analysed as

- i Topic element (specifier of CP)

- two Finite-verb form (C=head of CP) i.east. verb-second

- 3 Balance of the clause

In embedded clauses, the C position is occupied by a complementizer. In well-nigh Germanic languages (but non in Icelandic or Yiddish), this generally prevents the finite verb from moving to C.

- The construction is analysed equally

- 1 Complementizer (C=head of CP)

- 2 Bulk of clause (VP), including, in High german, the subject.

- iii Finite verb (V position)

This analysis does non provide a structure for the instances in some language of root clauses after bridge verbs.

- Example: Danish 6 ved at denne bog har Bo ikke læst with the object of the embedded clause fronted.

- (Literally 'We know that this book has Bo not read')

The solution is to permit verbs such as ved to accept a clause with a 2d (recursive) CP.[31]

- The complementizer occupies C position in the upper CP.

- The finite verb moves to the C position in the lower CP.

See also [edit]

- 2d position clitics

Notes [edit]

- ^ For discussions of the V2 principle, come across Borsley (1996:220f.), Ouhalla (1994:284ff.), Fromkin et al. (2000:341ff.), Adger (2003:329ff.), Carnie (2007:281f.).

- ^ Ehalka, Martin (2006), "The Word Society of Estonian: Implications to Universal Language", Journal of Universal Language, vii: 49–89, doi:10.22425/jul.2006.7.1.49, S2CID 52222499, Corpus ID: 52222499

- ^ Woods, Rebecca; Wolf, Sam (2020). Rethinking Verb 2d. Oxford University Press.

- ^ The examples are discussed in König and van der Auwera (1994) in the capacity devoted to each linguistic communication.

- ^ These and other examples are discussed in Fagan (2009)

- ^ Similar examples to these and others are discussed in Zwart (2011)

- ^ Zwart (2011) p. 35.

- ^ "Colloquium Neerlandicum 16 (2006) · DBNL".

- ^ See Thráinsson (2007) p.19.

- ^ Examples from Fischer et al (2000) p.112

- ^ encounter König & van der Auwera (1994) p.410

- ^ Forest, Rebecca (March 25, 2020), "A different perspective on embedded Verb Second", Rethinking Verb Second, Oxford University Printing, pp. 297–322, doi:10.1093/oso/9780198844303.003.0013, ISBN978-0-19-884430-iii , retrieved April 30, 2021

- ^ Woods, Rebecca (March 25, 2020), "A different perspective on embedded Verb Second", Rethinking Verb Second, Oxford University Printing, pp. 297–322, doi:10.1093/oso/9780198844303.003.0013, ISBN978-0-19-884430-iii , retrieved April thirty, 2021

- ^ Walkden, George (February 16, 2017). "Language contact and V3 in Germanic varieties new and old". The Periodical of Comparative Germanic Linguistics. twenty (i): 49–81. doi:10.1007/s10828-017-9084-ii. ISSN 1383-4924.

- ^ Jouitteau, Mélanie (March 25, 2020), "Verb 2nd and the Left Edge Filling Trigger", Rethinking Verb Second, Oxford Academy Press, pp. 455–481, doi:10.1093/oso/9780198844303.003.0019, ISBN978-0-xix-884430-3 , retrieved April 30, 2021

- ^ Urk, Coppe van (March 25, 2020), "Verb Second is syntactic", Rethinking Verb Second, Oxford University Press, pp. 623–641, doi:10.1093/oso/9780198844303.003.0026, ISBN978-0-nineteen-884430-3 , retrieved April xxx, 2021

- ^ Come across Fischer et al. (2000: 114ff.) for discussion of these and other examples from Erstwhile English and Middle English language.

- ^ Harbert (2007) p. 414

- ^ Inversion is discussed in Peters (2013)

- ^ come across Rowlett (2007:4)

- ^ run across Posner (1996:248)

- ^ Nichols, Johanna. (2011). Ingush Grammer. Berkeley: The University of California Press. Pp. 678ff.

- ^ Zepeda, Ofelia. (1983). A Tohono O'odham Grammar. Tucson, AZ: The Academy of Arizona Press.

- ^ Liver 2009, pp. 138

- ^ Vihman, Virve-Anneli; Walkden, George (2021). "Verb-second in spoken and written Estonian". Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics. 6 (1). doi:10.5334/gjgl.1404. ISSN 2397-1835.

- ^ Meelen, Marieke (March 25, 2020), "Reconstructing the rise of Verb 2d in Welsh", Rethinking Verb Second, Oxford University Press, pp. 426–454, doi:10.1093/oso/9780198844303.003.0018, ISBN978-0-xix-884430-3 , retrieved April 29, 2021

- ^ Andrason, Alexander (March 25, 2020), "Verb 2d in Wymysorys", Rethinking Verb 2d, Oxford Academy Press, pp. 700–722, doi:10.1093/oso/9780198844303.003.0030, ISBN978-0-xix-884430-three , retrieved April 29, 2021

- ^ Galves, Charlotte (March 25, 2020), "Relaxed Verb Second in Classical Portuguese", Rethinking Verb 2nd, Oxford Academy Printing, pp. 368–395, doi:10.1093/oso/9780198844303.003.0016, ISBN978-0-19-884430-iii , retrieved April 29, 2021

- ^ For an example of a DG analysis of the V2 principle, see Osborne (2005:260). That DG denies the existence of a finite VP constituent is apparent with most any DG representation of sentence structure; finite VP is never shown as a complete subtree (=constituent). See for instance the trees in the essays on DG in Ágel et al. (2003/2006) in this regard. Concerning the strict denial of a finite VP elective, encounter particularly Tesnière (1959:103-105).

- ^ See particularly: Hubert Haider, The syntax of German, Cambridge Academy Press, 2010

- ^ Sten Vikner: Sten Vikner: Verb movement and expletive subjects in the Germanic languages. Oxford University Press, 1995.

Literature [edit]

- Adger, D. 2003. Cadre syntax: A minimalist arroyo. Oxford, UK: Oxford Academy Press.

- Ágel, V., L. Eichinger, H.-W. Eroms, P. Hellwig, H. Heringer, and H. Lobin (eds.) 2003/vi. Dependency and valency: An international handbook of contemporary research. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Andrason, A. (2020). Verb second in Wymysorys. Oxford University Press.

- Borsley, R. 1996. Modern phrase structure grammar. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers.

- Carnie, A. 2007. Syntax: A generative introduction, 2nd edition. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

- Emonds, J. 1976. A transformational approach to English syntax: Root, structure-preserving, and local transformations. New York: Academic Printing.

- Fagan, Southward. Yard. B. 2009. High german: A linguistic introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Printing

- Fischer, O., A. van Kermenade, W. Koopman, and W. van der Wurff. 2000. The Syntax of Early English language. Cambridge: Cambridge Academy Press.

- Fromkin, V. et al. 2000. Linguistics: An introduction to linguistic theory. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers.

- Harbert, Wayne. 2007. The Germanic Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hook, P. E. 1976. Is Kashmiri an SVO Language? Indian Linguistics 37: 133–142.

- Jouitteau, M. (2020). Verb 2d and the left edge filling trigger. Oxford University

- Liver, Ricarda. 2009. Deutsche Einflüsse im Bündnerromanischen. In Elmentaler, Michael (Hrsg.) Deutsch und seine Nachbarn. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-3-631-58885-7

- König, Due east. and J. van der Auwera (eds.). 1994. The Germanic Languages. London and New York: Routledge.

- Liver, Ricarda. 2009. Deutsche Einflüsse im Bündnerromanischen. In Elmentaler, Michael (Hrsg.) Deutsch und seine Nachbarn. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

- Meelen, G. (2020). Reconstructing the rise of verb second in welsh. Oxford Academy Press.

- Nichols, Johanna. 2011. Ingush Grammar. Berkeley: University of California Printing.

- Osborne T. 2005. Coherence: A dependency grammar assay. Sky Periodical of Linguistics 18, 223–286.

- Ouhalla, J. 1994. Transformational grammar: From rules to principles and parameters. London: Edward Arnold.

- Peters, P. 2013. The Cambridge Dictionary of English Grammar. Cambridge: Cambridge University Printing.

- Posner, R. 1996. The Romance languages. Cambridge: Cambridge Academy Press.

- Rowlett, P. 2007. The Syntax of French. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- van Riemsdijk, H. and E. Williams. 1986. Introduction to the theory of grammar. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Tesnière, 50. 1959. Éleménts de syntaxe structurale. Paris: Klincksieck.

- Thráinsson, H. 2007. The Syntax of Icelandic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Walkden, G. (2017). Language contact and V3 in germanic varieties new and old. The Journal of Comparative Germanic Linguistics, twenty(one), 49-81.

- Woods, R. (2020). A different perspective on embedded verb second. Oxford Academy Press.

- Woods, R., Wolfe, due south., & UPSO eCollections. (2020). Rethinking verb second (First ed.). Oxford Academy Press.

- Zwart, J-West. 2011. The Syntax of Dutch. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Subordinate Clauses Represent Complete Thoughts,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/V2_word_order

Posted by: tamplinconelays.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Subordinate Clauses Represent Complete Thoughts"

Post a Comment